Beatrix to Barklem: Of Mice and (Wo)men

- robyncoombes

- Nov 13, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2023

Fig. 1. Beatrix Potter, The Mice at Work: Threading the Needle. c. 1902. Ink, watercolour and gouache on paper, 111 x 92 mm. The Tate, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/potter-the-mice-at-work-threading-the-needle-a01100.

Having spent four years at art college prior to studying English, I often like to consider books from a visual as well as literary perspective. After all, most of our first memories of books centre those vivid primary colours and world-building illustrations that, for me at least, have sustained a lifelong love of reading. I have a photograph of my toddler self rapt in a Richard Scarry book so big only my chubby hands are visible, and another where I’m shamelessly scribbling on a squirrel in a turquoise water-coloured landscape. Yes, this last one sounds like a fever dream, and if it weren’t for the (blurry) photographic evidence of the little vandal in action, I probably would have gaslit myself into thinking so. This particular book was sadly lost to the ravages of times, and frustratingly, I couldn’t for the life of me remember the title, subject matter, or any detail other than the vivid red, yellow, and green pictures. It fascinates me how memories of those formative reading experiences stay with us, and warp over time, until maybe a colour, an animal, or even a feeling lodges deeply to resurface later. Only a dodgy memory remained of that book, so in a fit of nostalgia, I googled one day until my ridiculous word combinations finally struck gold. At last the victim of my delinquent doodling was restored to me. The book in question: Tufty’s Pot of Paint.

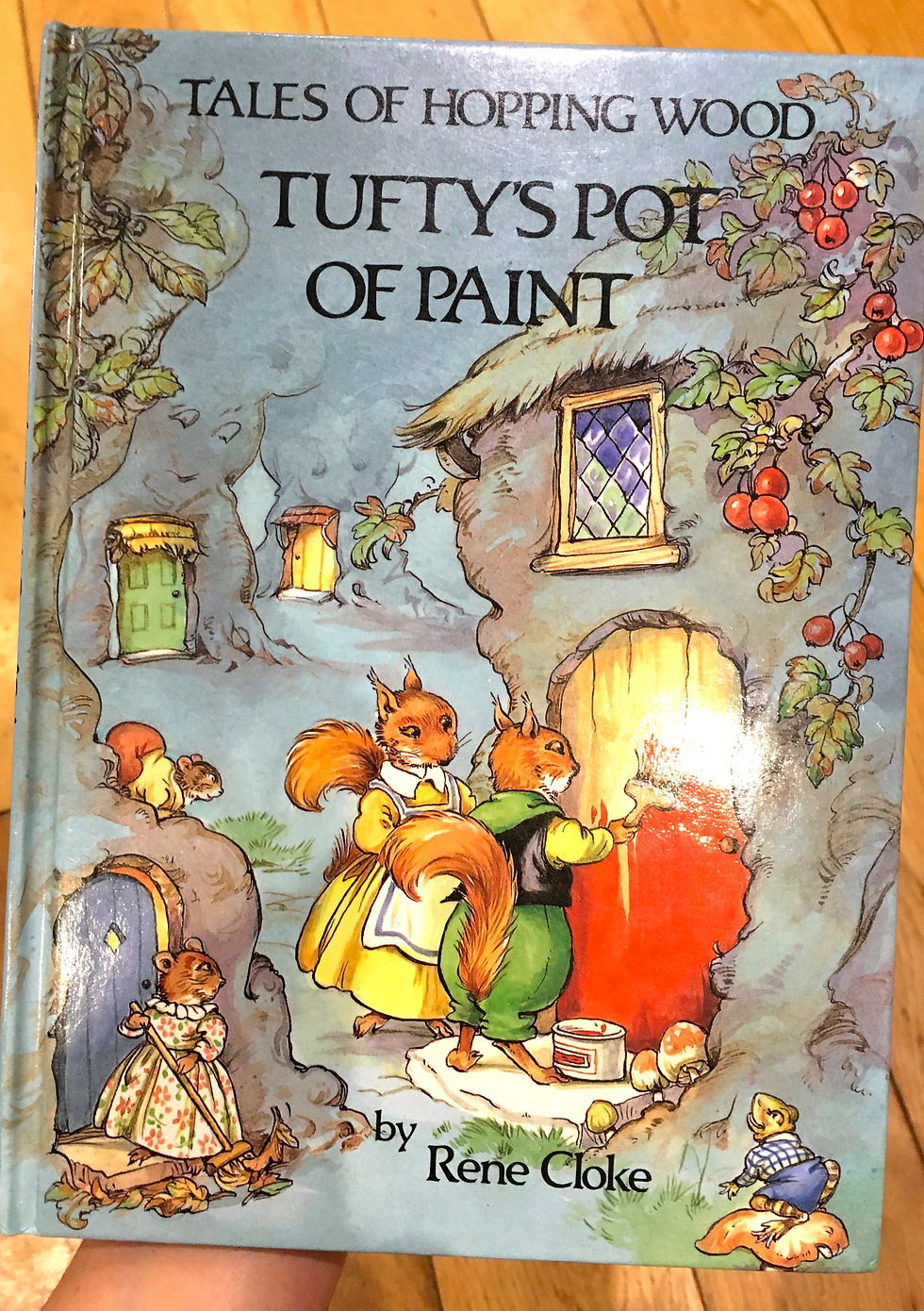

Fig. 2. Cover Illustration; Rene Cloke,Tufty’s Pot of Paint, (Award Publications, 1988).

I had a little giggle. Was it exactly what I remembered? Most things never are and this was no exception. While definitely recognisable, in the intervening years an uncanny defamiliarization had taken place. Maybe owing to a slight evolution in my artistic tastes, the illustrations were not what I expected. But it was still a cute animal story with some evocative endnotes and squirrels in human garb painting their front doors red. What more could a child want?

I have often wondered why children’s books have such strong connections to animals and the natural world, whereas adult literature often assumes a more anthropocentric viewpoint. As an adult now, I hold on to illustrated children’s books, lest I have a repeat of the Tufty’s-Pot-of-Paint-debacle (God forbid). Two of these books in question definitely hold up to any standards of excellence, and as a keen watercolourist myself, I often turn to them for inspiration. In a similar vein to Rene Cloke’s squirrel DIYers, both of the books I am discussing today portray anthropomorphised animals living in microcosmic communities. Beatrix Potter and Jill Barklem produced incredible artwork for children, one at the beginning, and the other towards the end, of the 20th century. As female author/illustrators, they were perhaps best positioned to navigate the child/nature connection.

David Rudd summarises the chronology of children’s animal stories, and traces their affiliation from Aesop’s fables to the Romantic and Rousseauvian notions of innate childhood innocence and naturalness, before dating the child/nature association back to the 4th century BCE and Aristotle’s claims that “a child differed little from an animal” (242). As Peter Hunt reminds us, “children’s books – from writing to publication to interaction with children – are the province of that culturally marginalised group, females” (1), while Sherry B. Ortner asserts that women are simultaneously active members of culture and more closely linked to nature (12). As women have historically been assigned the cultural task of educating children, it is interesting to examine how these two female author/illustrators, working on either side of the century, variously represent the natural world for a child audience.

Beatrix Potter published The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1902, and Jill Barklem’s first Brambly Hedge book was published in 1980. Both working in watercolour and depicting communities of animals, Potter diversifies her animal networks to include ducks, cats, badgers, foxes, rabbits, and rodents, while Barklem sticks to cute English dormice. Despite some similarity in subject matter and medium, the authors diverge in other respects. Whereas Barklem represents a cosy, homely, and bucolic civilisation, Potter often explores scary themes and childhood anxieties through predator-prey relationships, and the restriction of Victorian society. The sartorial constriction she projects onto animals, (brilliantly evoked in The Tale of Tom Kitten), comically, or otherwise, highlights the plight of corseted, bustled, and petticoated women of the period. As Carole Scott points out, “clothing marks the point at which the individual and the social world touch …[f]or children who are in the process of developing self-definition, clothes are a very personal and immediate experience of their relationship to the world around them” (“Between Me and the World”, 192). Another scholar notes that this often has a satirical undertone, where “the pretensions of etiquette and the practice of civility … are often little more than a veneer to disguise animal drives, desires, and instincts” (Evans 605). For Scott, and I would have to agree, Potter’s portrayals of humanised animals in waistcoats and bonnets evokes the contrivance and “discontents of civilization” (“Clothed in Nature”, 77). This could be construed as a warning signal, or a life lesson, for children who find themselves already anxious about the world of grown-ups. These worries find a fitting metonymy in the increasingly restrictive clothing that marks the progression from childhood to adulthood.

Fig. 3. The restriction of female clothing is accentuated by forcing mice into human attire; Jill Barklem, “Autumn Story.” The Complete Brambly Hedge, (HarperCollins 2020), p. 97.

Of course, Potter’s animals are not all fully anthropomorphised. Some do choose to fully adopt human fashion and in so doing lose their animality – as Mr Tod, a fox, wears a three-piece suit he therefore becomes “a thin-legged person” (The Tale of Mr. Tod, n.p.). But others remain unclothed (which nearly demanded censorship in the case of Tom Kitten, as Peter Hunt informs us (6)). Yet a third class of characters presents a hybrid mix between the two (Scott “Clothed in Nature”, 85). Peter Rabbit dons his blue jacket for special occasions but hops about unencumbered as most children prefer to do.

Scott considers The Tailor of Gloucester Potter’s accession to the positive possibilities of clothing, and highlights how this tale departs from her other depictions in some technical respects. Each painting is bordered with the metaphoric effect of an embroidery frame (“Clothed in Nature”, 86). She suggests that the Mayor’s coat is “an interesting example of the complex interweaving of nature and art where nature represented in one art form is transmuted into yet another” (71). Through the coat “of cherry-coloured corded silk embroidered with pansies and roses) and a cream-coloured satin waistcoat (trimmed with gauze and green worsted chenille)” (Tailor 10-15), Potter brings the sartorial delights of the Victoria and Albert Museum (where she found inspiration for Tailor) to life through her experience in botanical painting. Scott contends that the watercolours meld the worlds of human, non-human animals, and plants, allowing children to imagine a harmonious world where hierarchies are levelled and the boundaries of human and nature are questioned (“Clothed in Nature” 70).

This provides an interesting contrast to Barklem’s illustrations, where animals are wholly anthropomorphised and ‘civilised’, existing in miniature communities of, to all intents and purposes, human behaviour and interaction. Fully-clothed, employed, and civically minded, these mice are industrious home-makers in quintessential English country settings, complete with class hierarchies. Beautifully and intricately wrought, Barklem’s highly-detailed watercolours could take up to three months to complete (“How It All Began”). The author states that many of her inspirations came from Britain’s agricultural past – “[t]he harnessing of wind and waterpower, the imaginative use of ingredients, the preserving of fruits in the autumn for winter use, the ceremonies and celebrations that mark the turning points of the year” (“How It All Began”). She renders with incredible skill the ingenuous contraptions of mice, while always maintaining a sense of their scale. Barklem explains that her process involved “eliminat[ing] human concepts” by devising “a system of measurement based on tails and paws rather than feet and inches. Weight is measured with acorns and grains of wheat and time is measured with sundials, candle clocks and water clocks” (Introduction, 7). Of course, imposing human time, habitations, industry, and clothing on the animal world might not align with an elimination of human concepts, but this perspective shift allows children to consider a world outside of their own and value the merit and intelligence (if imposed and fictionalised by a human author) of nonhuman animals.

Fig. 4. Dissecting the landscape allows us to peek into the imaginative and secret world of mice; Jill Barklem, “Spring Story.” The Complete Brambly Hedge, (HarperCollins 2020), p.12.

Many of Barklem’s illustrations involve transverse sections of the landscape where she effectively ‘chops’ through trees or nests to reveal a secret life within. This is what Susan Stewart calls the “constant daydream” of the miniature, which offers “a narrativity and history outside the given field of perception” leading to “significance multiplied infinitely within significance” (54).

Fig. 5. Transverse section illustration revealing a secret inner world; Jill Barklem, “Autumn Story.” The Complete Brambly Hedge, (HarperCollins 2020), p. 82.

“There are no miniatures in nature; the miniature is a cultural product” (Stewart 55) - yet Barklem figures a child-friendly conception of the vast complexity of life outside of our narrow human understanding. Both author/illustrators then, have left not only an artistic legacy, but opened imaginative worlds for generations of children to consider our links to nature. Both Potter and Barklem convey the intricacy of the natural world, not as the binary opposite to human, but as an ecosystem closely interlinked with our daily lives, and one we have far more to learn about in order to understand ourselves.

Works Cited

Barklem, Jill. The Complete Brambly Hedge, HarperCollins, 2020.

Cloke, Rene. Tufty’s Pot of Paint. Award Publications, London, 1988.

Evans, Heather A. “Kittens and Kitchens: Food, Gender, and ‘The Tale of Samuel

Whiskers.’” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 36, no. 2, 2008,

pp. 603–23. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40347207.

“How It All Began.” Brambly Hedge, www.bramblyhedge.com/our-story/.

Hughes, Kathryn. "Review: Arts: Run Rabbit Run . . .: Beatrix Potter Isn't all

Fluffy Animals and Cosy Interiors. There's Danger Lurking Everywhere.

Kathryn Hughes on the Amateur Watercolourist Who Stormed the Nursery."

The Guardian, Oct 08, 2005, pp. 1-4. ProQuest, www-proquest-com.ucc.idm.oc

lc.org/newspapers/review-arts-run-rabbit-beatrix-potter-isnt-all/docview/2463

46771/se-2.

Hunt, Peter. “Introduction: The Expanding World of Children’s Literature Studies.”

Understanding Children’s Literature, edited by Peter Hunt, Taylor & Francis, 2005,

pp. 1-14. ProQuest, www.ebookcentral-proquest-com.ucc.idm.oclc.org/lib/uccie-eb

ooks/detail.action? docID=259048.

Kutzer, M. D. "A Wildness Inside: Domestic Space in the Work of Beatrix Potter."

The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 21, no. 2, 1997, pp. 204-214. ProQuest, www.pr

oquest.com/scholarly-journals/wildness-inside-domestic-space-work-beatrix.d

Nodelman, Perry. “Pictures, Picture Books, and the Implied Viewer.” Words about

Pictures: Narrative Art of Children's Picture Books, University of Georgia Press,

1990, pp. 11-35.

Ortner, Sherry B. “Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?” Feminist Studies, vol. 1,

no. 2, 1972, pp. 5–31. JSTOR, doi.org/10.2307/3177638.

Potter, Beatrix. Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature. 12 Feb. 2022 - 8 Jan. 2023, The Victoria and Albert

Museum, London.

---. The Tailor of Gloucester. 1903. Frederick Warne & Co, New York, 1931, pp. 1-85.

---. The Tale of Mr. Tod. Frederick Warne & Co, 1912.

---. The Tale of Tom Kitten. Frederick Warne & Co, 1907.

Rudd, David. “Animal and Object Stories.” The Cambridge Companion to Children’s

Literature. Cambridge UP, 2009, pp. 242-257.

Scott, Carole. "Clothed in Nature or Nature Clothed: Dress as Metaphor in the

Illustrations of Beatrix Potter and C. M. Barker." Children's Literature, vol. 22,

1994, p. 70-89. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/chl.0.0559.

---. “Between Me and the World: Clothes as Mediator between Self and Society in the

Work of Beatrix Potter.” The Lion and the Unicorn (Brooklyn), vol. 16, no. 2, 1992,

pp. 192-198.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir,

the Collection. Duke UP, 1993.

Comments