Abstract to Somewhat Illustrated

- robyncoombes

- Apr 10, 2023

- 19 min read

Updated: Apr 11, 2023

The journey so far in E-Portfolio form!

Many months ago we were tasked with creating a blog that would track our development as postgraduate students, exploring possible thesis topics, or new areas of research interest. And what a venture it’s been. I’d like to say I covered everything on my preliminary plan of action, but in reality I was a little over-ambitious in my aims. At least I have the next several years of inspiration roughly sketched out. Top of my priorities was a (shallow) dive into Children’s Literature, beginning with the art of picture books and explorations of my favourite illustrations from the likes of …

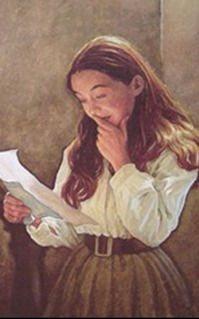

P.J. LYNCH

Fig. 1. You can always gauge an artist's skill is by their ability to draw hands! When Jessie Came Across the Sea, written by Amy Hest, illustrated by P.J. Lynch, Walker Books, 1997.

NICK BUTTERWORTH

Fig. 2. One Snowy Night by Nick Butterworth, published by HarperCollins, 1989

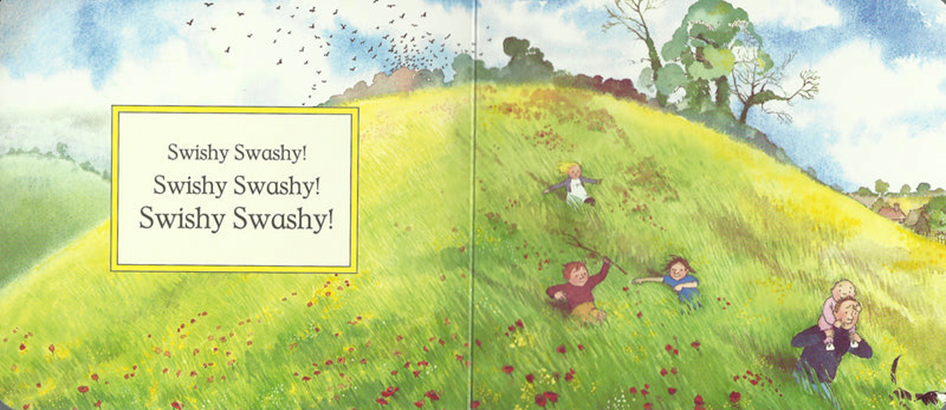

HELEN OXENBURY

Fig. 3. Illustrations by Helen Oxenbury for Michael Rosen’s We’re Going on a Bear Hunt, Simon and Schuster, 1989.

JESSICA LOVE

Fig. 5. Left: Jessica Love’s vibrant illustrations in Julian is a Mermaid, Candlewick Press, 2018.

Below: Julian at the Wedding is similarly luminous with gouache on brown paper paintings, Walker Books, 2020

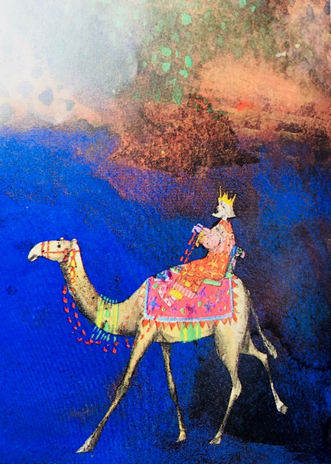

BRIAN WILDSMITH

Fig. 6. Brian Wildsmith’s gemlike colours and unique style in A Christmas Story, Oxford UP, 1989

and of course, QUENTIN BLAKE

Fig. 7. Iconique; one of my favourite Quentin Blake’s displaying Trunchbull’s shotput skills,

from Roald Dahl’s Matilda, 1988

I wanted to explore their anthropomorphism and depictions of the natural world, while considering larger themes of nostalgia and the miniature. Then ideally, I would move on to book series, (especially hyper-productive authors and the phenomenon of such Scholastic staples as The Baby-Sitter’s Club and Goosebumps), looking next at L.T. Meade, another incredibly prolific writer of well over 200 girls’ stories who was born in my hometown in 1844. Perhaps, having read none of Baby-Sitter’s, one Goosebumps, and half of Meade’s not-quite-to-my-taste Wild Kitty, it was for the best this plan never came to fruition.

Fig. 8. Image from The Irish Times, 26 Oct. 2014, www.irishtimes.com/culture/books/lt-meade-the-jk-rowling-of-her-day-remembered-100-years-on-1.1977221.

Fig. 9. Image from World of Blyton, www.worldofblyton.com/2019/03/07/malory-towers-covers-through-the-years/.

Next up in my hypotheticals would be school stories, spanning Blyton’s probably problematic Malory Towers to more modern iterations. Of course witches needed a mention, from Winnie the Witch to The Worst Witch, and my favourite Pongwiffy, then perhaps to the allure of horse books from Sheltie to Heartland and why just about every 12-year old girl (myself included) is drawn to this giant subgenre before we’ve learnt to cringe at cheesy book titles. And on I could go into the mists of school library back catalogues.

Fig. 10. Illustrations by Chris Smedley, published by Puffin Books, 1992-1996

Fig. 11. Peter Clover, I smell a pseudonym

Fig. 12. Healing horses, healing hearts … 😳

But instead, I ended up writing about ‘Peter Pan & Wendy: The Uncanniness of 'Writing-Back', after our first module, Theories in Modernity, brought us on a wild ride through Freud’s Unheimliche. I focused on the Uncanny’s defamiliarisation as an element of books that ‘write back’, considering those repressions in an original text that often come to light in their re-visionary responses. Some of the uncanny parallels across these texts (Karen Wallace’s Wendy and Barrie’s Peter Pan) were the oedipal fusions of Mr Darling/Hook, and the doubling of Peter and Wendy’s neurodivergent brother, Thomas.

“Wallace chooses to fuse Hook and Mr Darling. Like Jekyll and Hyde, Wendy knows only too well her father can flip from “his pink, smooth morning face as he left for the office” to his blotchy “evening face” that seems to be (uncannily?) “made of wax” (25). Furthermore, Letitia and Henry Cunningham, the children of George Darling’s ‘mistress’, are the pantomime doubles and forced playmates of his own Darling children. These untamed and animalistic foils are likened to jungle animals; coiled snakes and imperial horrors intent on playing “Bloody Slaughter” with their toy ‘cowboys and Indians’ (35-6). Letitia is clearly the Tiger Lily of Barrie’s tale, but instead of humanising his imperialist trope, Wallace leans into the colonial metaphors and presents her as the dangerous, “unusual and exotic” (36) tiger cub waiting to bare her teeth into her Nanny’s hand. Meanwhile her brother Henry is a more damning portrait of Barrie’s band of pirates, intent on enacting violent scalpings. Both satirise the innocence of childhood and condemn the British imperial project, while at the same time transposing the violence onto American cowboys instead of English gentlemen.”

“Peter Pan & Wendy: The Uncanniness of 'Writing-Back'”. Robyn Coombes. 2 November, 2022.

I did manage to squeeze in the afore-mentioned ‘miniature’ when considering Wendy’s dollhouse, so I suppose I could cross that off the list …

“In microcosmic form, Wendy’s doll’s house miniaturises and summons the dreamlike safety of their uncle’s idyll [the stand-in for Neverland] whenever they need it. Perhaps there are elements of Susan Stewart’s contention that the “terrifying and giganticized nature of the sublime is domesticated into the orderly and cultivated nature of the picturesque” (75). Those sublime, incomprehensible feelings when youth is prematurely confronted with adult reality, seeks safety in the manageable form of the picturesque doll’s house.”

“Peter Pan & Wendy: The Uncanniness of 'Writing-Back'”. Robyn Coombes. 2 November, 2022.

Next up on my children’s-lit-bucket-list was ‘Beatrix to Barklem: Of Mice and (Wo)men’, one of my favourite blogs to write, which compared and contrasted two incredible female writer/illustrators and their iconic watercolour worlds.

“Whereas Barklem represents a cosy, homely, and bucolic civilisation, Potter often explores scary themes and childhood anxieties through predator-prey relationships, and the restriction of Victorian society. The sartorial constriction she projects onto animals, (brilliantly evoked in The Tale of Tom Kitten), comically, or otherwise, highlights the plight of corseted, bustled, and petticoated women of the period. As Carole Scott points out, “clothing marks the point at which the individual and the social world touch …[f]or children who are in the process of developing self-definition, clothes are a very personal and immediate experience of their relationship to the world around them” (“Between Me and the World”, 192). Another scholar notes that this often has a satirical undertone, where “the pretensions of etiquette and the practice of civility … are often little more than a veneer to disguise animal drives, desires, and instincts” (Evans 605). For Scott, and I would have to agree, Potter’s portrayals of humanised animals in waistcoats and bonnets evokes the contrivance and “discontents of civilization” (“Clothed in Nature”, 77).”

“Beatrix to Barklem: of Mice and (Wo)men.” Robyn Coombes. 13 November, 2022.

Fig. 13. The restriction of female clothing is accentuated by forcing mice into human attire; Jill Barklem, “Autumn Story.” The Complete Brambly Hedge, HarperCollins, 2020, p. 97.

In discussing my favourite Potter story, The Tailor of Gloucester, I was able to combine my love of embroidery and illustration, in what Carole Scott argues is Potter’s melded worlds of human, non-human animals, and plants, allowing children to imagine a harmonious world where hierarchies are levelled and the boundaries of human and nature are questioned (“Clothed in Nature” 70). But I also found that Barklem’s exquisitely intricate watercolours, depicting the bucolic countryside escapades of mice, allow children to shift their concepts of scale and imagine the innate significance of ‘all creatures great and small’.

“Many of Barklem’s illustrations involve transverse sections of the landscape where she effectively ‘chops’ through trees or nests to reveal a secret life within. This is what Stewart calls the “constant daydream” of the miniature, which offers “a narrativity and history outside the given field of perception” leading to “significance multiplied infinitely within significance” (54).”

“Beatrix to Barklem: of Mice and (Wo)men.” Robyn Coombes. 13 November, 2022.

Apparently the miniature can definitely be crossed off my list.

Fig. 14. Dissecting the landscape allows us to peek into the imaginative and secret world of mice; Jill Barklem, “Spring Story.” The Complete Brambly Hedge, HarperCollins, 2020, p.12.

Between these analyses of children’s books came a very interesting seminar by Holly Walker-Dunseith, which made me consider her work on Biddy Early, Lady Gregory, and W.B. Yeats, in the context of Victorian botany. In ‘Biddy Early, Herbal Healers, and Women of Botany’, I took Early’s famous moss cure as my starting point to examine the importance of the plant in The Signature of All Things, and the women folk healers of Hannah Kent’s The Good People (2016).

“Set prior to the famine, from 1825-6, each chapter is named after a plant traditionally used for medicinal purposes, from the familiar dock, bramble, and nettle, to the lesser-spotted Devil’s-bit scabious. Intertwined with poverty, hunger, and elemental hardship, Kent fuses holistic folk-belief and fairy lore with everyday survival, reflecting the syncretic reality of nineteenth-century life which she calls “a deeply complex, ambiguous system” with “little that is twee or childish about it” (384). Her research lists Lady Gregory’s fairy stories amongst a bibliography of other texts on Irish myths, legends, and healing practices.”

“Seminar Series 1: Biddy Early, Herbal Healers, and Women of Botany.” Robyn Coombes. 11 November, 2022.

Meanwhile, Gilbert’s Signature, centres

“the unconventional life of Alma Whittaker, whose life begins in 1800, spans eighty years of the 19th century, and becomes devoted to the study of moss. Alma is presented as the fictional contemporary and competitor of Charles Darwin who publishes On the Origin of Species before she finishes her magnum opus, The Theory of Competitive Alteration. With her similar arguments on natural selection now rendered obsolete, Gilbert further suggests that it was Alma’s female tendency for empathy and perfectionism which prevented her from publishing. As she explicitly states in the same interview; “what holds women from putting their work forward is a fear that it is not immaculate, not beyond reproach and that it may not be taken seriously” (Dreifus).”

“Seminar Series 1: Biddy Early, Herbal Healers, and Women of Botany.” Robyn Coombes. 11 November, 2022.

Already in this (E)arly blog, I can see the seeds of my thesis and mini-conference germinating, with my inclusion of Ann B. Shteir’s fascinating essay on 19th-century botany which certainly informs my later research.

Departing somewhat from plants, my next blog was a ‘Pelisse Inspection of Mansfield Park’. This allowed me to (self-indulgently) combine my past in costume design with everything I was learning on our Romanticism module. Relating the novel to its 1999 film adaptation I considered

“the visibly decaying edifice of … Rozema’s film [which] overtly ties the estate’s near ruin to the crumbling conventions it’s built upon. Mansfield’s sister estate in Antigua, and the transactional marriages of the young Price/Bertrams, are figured as the unstable and dangerous institutions we now know them to be, with the hindsight of two centuries. Released six years after Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism with its famous chapter on Mansfield Park (“Jane Austen and Empire”), Rozema course corrects on the theme of slavery so inherent in the novel’s name.”

“Pelisse Inspection of Mansfield Park.” Robyn Coombes. 19 November 2022.

Part of my ‘pelisse’ interrogation, was an analysis of the silent slavery in the novel and its explicit rendering in the film, while relating these themes to the use of costume. My ramble included everything from Rozema’s feminist makeover of Fanny, to her substitution of Susan for William, and the impact this fraternal elision has on the central romantic, but cousinly, relationship, citing Glenda Hudson’s “Incestuous Relationships: Mansfield Park Revisited”. I tied up proceedings by considering how Rozema’s costumes allow her audience to ‘in-habit’ Austen’s characters ...

“because it is in seeing characters wear those habits of the Regency era, that we fully appreciate the constraints on behaviour and character. In the 1999 film, Fanny is not the frail, headache-prone character of the novel, but a lively protagonist who could lend her name to the film’s title. I would argue this has much to do with the film’s use of costume, which can often be forgotten in modern readings of Austen. The Regency age of fashion was a little less restrictive than popular opinion might have you believe. Corsets, or stays as they were then called, were more of a personal preference than an imperative, and not necessarily worn on an everyday basis owing to the new style of bodice which modelled itself on neo-classical empire lines.”

“Pelisse Inspection of Mansfield Park.” Robyn Coombes. 19 November 2022.

While Fanny wears freeing apron-style dresses, Mary wears ...

“exclusively dark navy and black, with white collars and lacy sleeves, … [fashioning] herself as an object of desire that appeals especially to Edmund as a sort of feminine counterpart to the clergyman’s robes.”

“Pelisse Inspection of Mansfield Park.” Robyn Coombes. 19 November 2022.

Fig. 15. Still of Mary Crawford in secular monochrome from Mansfield Park by Patricia Rozema, 1999, cinematography by Michael Coulter.

“But it is Mr Rushworth’s appearance that perfectly encapsulates all that is glorious and ridiculous in some of Austen’s male characters … here translated into Beau Brummell’s mirror image, complete with his, let’s just say, distinct, hairstyle.”

“Pelisse Inspection of Mansfield Park.” Robyn Coombes. 19 November 2022.

Fig. 16. Still of Mr Rushworth’s Beau Brummell coiffure from Mansfield Park by Patricia Rozema, 1999, cinematography by Michael Coulter.

Keeping with the Mansfield theme while writing an essay on the novel, one of my subsequent blogs attempted to redeem the oft-maligned Ms Price. In ‘The Critics vs Fanny Price’, I regret to say I became a keyboard warrior, fighting the likes of Nietzsche’s moralistic insults, and Nina Auerbach’s vampiric aspersions, while challenging the regularly ableist language used to demonise her. Quickly becoming a cauldron of contempt, I tempered the spice with some of the other research that didn’t quite fit my essay title. In the mix was Kathryn Sutherland’s analysis of ‘heritage movies’ and their move towards an Austenian minimalism in which

“the same stately piles are “emptier and draughtier, their rooms less opulent, their furnishings competing less for our attention” (Sutherland 223) …“Austen’s brand of realism”, does not privilege the visual (215); rather “she wishes to throw the emphasis of understanding upon hearing, the faculty that in eighteenth-century aesthetics was associated with the social passions of sympathy, shared values and custom” (216).

“The Critics vs Fanny Price.” Robyn Coombes. 6 December, 2022.

Rozema’s Mansfield Park, I argued, conforms to this ‘realism’ by disrupting Austen’s narrative form, breaking the fourth wall, and inviting us in to share Fanny Price’s spectatorship.

“Her moral gaze is what disconcerts us in the modern age, but the film’s defiance of that imaginary wall, highlights the meta-theatricality and artificiality that abounds in the novel – the play-within-the-play/film that sparks the plot, and the pretence of all its main players.”

“The Critics vs Fanny Price.” Robyn Coombes. 6 December, 2022.

Sandwiched between the bread of Austen, I blogged about ‘Retro-Spectres’ in the light of Rita Kelly’s luminous research seminar, and her eloquent connections between poetry, temporality, and the unconscious influences on a writer’s work.

“While Kelly reminded us that the author “gives to airy nothing/A local habitation and a name” (“A Midsummer Night’s Dream” 5.1.16-17), once named it goes forth into the world with an independence and autonomy that no longer requires the authorial figure, and even scorns authorial intent. The first line of every story too, according to Kelly, becomes a ghost and must be discarded. Returning to her title – “Revisiting Thus the Glimpses of the Moon” – Kelly seems to identify with Hamlet’s sublunary experience at Elsinore (1.4.53). Referring to Hamlet senior’s revisiting ghost, Kelly expanded the quote to encompass that sublime sense we often feel in the presence of a full moon, when we seem to know that what we are doing is worthwhile, and gain validation from nature’s supreme symbol of illumination in darkness.”

“Research Seminar 2: Retro-Spectres.” Robyn Coombes. 21 November, 2022.

On symbols of illumination, another favourite blog to write was ‘Fervent Fevers/Christian Consumptives: 19th Century Idols of Innocence’, in which I explored the “morbid fascination connecting those emblems of nineteenth-century fervid purity – Beth March (Little Women), Helen Burns (Jane Eyre), Dick and Oliver (Oliver Twist), and George Arthur (Tom Brown’s Schooldays).” I considered the common trope of the ‘cipher of virtue’ – those religious emblems, purified by fever and deified by death.

“Oliver … can easily be read through the Victorian obsession with childhood innocence, which brought to its extreme, culminates in the image of preservation through death – the most ‘angelic’ child is the dead child. Untouched by adversity, Oliver is an impenetrable shell despite the gothic forces surrounding him. At the novel’s opening, he even sleeps amongst the coffins of the Sowerberry’s establishment, and is later framed lying motionless on a curtained bed. In his lying-in-state, he is “a mere child, worn with pain and exhaustion and sunk into a deep sleep. His wounded arm … crossed upon his breast, and his head reclined … his long hair … streamed over the pillow” (238). This state of passivity and stasis suggests he could already be dead; he certainly escapes death many times and is described here in an image that reflects those deeply disturbing portraits of deceased children which so preoccupied the Victorians.”

“Fervent Fevers/Christian Consumptives: 19th Century Idols of Innocence.” Robyn Coombes. 23 November, 2022.

I contextualised these instances, of course, with the very real Victorian threat of childhood mortality and the virulence of tuberculosis/consumption, scarlet fever, and typhus, asking:

“did Oliver surmount his “considerable difficulty in … tak[ing] upon himself the office of respiration” (3) in Chapter One? As the liminal and mystical figure “poised between this world and the next” (3), Oliver highlights the high rate of fictional child mortalities across nineteenth-century literature. Just like Beth March, he too hovers between life and death, never fully occupying this world or a subjectivity of his own.”

“Fervent Fevers/Christian Consumptives: 19th Century Idols of Innocence.” Robyn Coombes. 23 November, 2022.

While Helen burns with “radiance” (and nominative determinism), as a symbol of “pure, full, fervid eloquence” (Bronte 75), I found that poor George Arthur of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, fits another angelic trope, that of the Angel in the House.

“It might be supposed that masculinity in a boys’ school is necessarily represented in a vacuum. Hughes’ influential school story after all “clearly functioned to create the gendered masculine subject” aligned with “imperial imaginaries” (Reimer 216). But while he takes a stand against the ‘fagging’ which continued into the 20th century, Hughes nevertheless depicts the deeply unsettling “small friend system” (182) … But these ‘Muscular Christian’ types – those “good English boys, good future citizens” (58), trained through rugby and Rugby to defend and expand the empire, are not really in a masculine vacuum. Their hapless victims, like Arthur (“a queer chum for Tom Brown” (174)), become the Angels in the House, as a sort of training ground for marriage. As Maureen M. Martin asserts, while “this homosocial network demanded heterosexuality of its adult members, it winked at the homosexual attachments and experiences” at public school (483-4). And Arthur as “embodiment of idealized femininity” provides Tom with “celestial help” (484).

“Fervent Fevers/Christian Consumptives: 19th Century Idols of Innocence.” Robyn Coombes. 23 November, 2022.

I argued that to allow Tom to leave this homosocial relationship behind and inherit the heterosexual world after matriculation, Arthur must succumb to his “tendency to consumption” (Hughes 187).

Succumbing to my fear of social media back in February was not an option, as we set off on a voyage of Wiki-editing and live-tweeting. I chose to update Wikipedia’s entry for Gaskell’s North and South to include its links to Pride and Prejudice, and this naturally led me to blog on the dichotomised geographies of Milton/Helstone and the industrial parallels to Austen’s picturesque landscapes. This certainly feeds into my current thesis direction, which builds on

“the difference between Austen’s Derbyshire and the “black sulphurous smoke” of Seward’s “To Colebrooke Dale”.”

“Wikipedia edit-a-thon.” Robyn Coombes. 8 February, 2023.

I combined these three texts to consider Lady Catherine’s famous question: “Are the shades of Pemberley to be thus polluted?” (ch. 56) as speaking more to Elizabeth’s muddy petticoats and threat of social contamination, than the very real pollution happening in Sheffield to the north or Coalbrookdale to the south-west. Having subsequently incorporated Seward's poem into my thesis research, it is interesting to trace the beginnings of my thoughts on Austen's Pemberley as a pristine greenhouse estate, narratively protected against the "wasted bloom" of "violated Colebrook" (Seward).

Fig. 17. Left: Still from North and South, directed by Brian Percival, BBC miniseries, 2004.

Margaret Hale in the cotton 'snow' of incipient

respiratory illnesses in Manchester's cotton mills.

Fig. 18. Below: Still from Pride and Prejudice, directed by Joe Wright, 2005.

Elizabeth Bennet in the hazy golden hour and grain particles of the idyllic rural south.

Closing off the research seminars I had time to write about, (Professor Lee Jenkins' fascinating talk on D.H. Lawrence will hopefully make its way onto the blog agenda), was Danny Denton’s ‘Being Present’. Though his demystification of world-building practices and hauntology were hugely thought-provoking, I knew as soon as podcasts were referenced, that I would be spring-boarding myself into an in-depth analysis of their relation to place and memory, and their potential to transform Augé's non-places into spaces of aural imagination and recollection. And leap I did into a forward pike towards hauntological, feminist, and literary podcasts which brought me full circle to

“Denton’s notion of ‘embodying’, wherein these aural spaces/non-places are inscribed with memories, ideas, and prospects of futures not yet lost to hauntology and failed capitalism. Those airports, garage forecourts and railway stations could perhaps be saved from cyclical, ghostly spaces of slipping time and grey concrete. (But only if you’re listening to “Werewolves: A Metaphor?”).”

“Research Seminar 1st Feb 2023 – Danny Denton.” Robyn Coombes. 15 February, 2023.

My final blog, before mini-conference fever set in, crystallised my thesis interests and certainly informed my April presentation. ‘Transcending Glass - The Greenhouse Effect on Page and Screen’ expands in some ways on my conference topic, by incorporating my exploration of the greenhouse’s liminal and symbolic role in literature, with its portrayal in period dramas.

“For some reason I’ve been fascinated by the role the glasshouse/conservatory, greenhouse/hothouse plays in both literature and screen depictions of the Romantic, Victorian, and Edwardian eras. Their decadence reads like a condensed pastoral idyll or preserved Eden - saturated colours and textures, gargantuan leaves and sumptuous flowers to hide behind (at least that’s my idea of Eden). The vines, roses, and ‘cottage-core’ creepers of the costume drama’s glasshouses make these cluttered spaces almost oppressively picturesque. But I’ve been wondering if there is more to the greenhouse, and why this space so often occurs in scenes of transgression and excess?”

“Transcending Glass - The Greenhouse Effect on Page and Screen.” Robyn Coombes. 31 Jan, 2023.

Fig. 19. Still from The Age of Innocence, directed by Martin Scorsese, Cappa Productions, 1993. You can almost get a headache from the stifling amount of flowers in every frame of Scorsese’s film. Mrs Manson Mingott’s conservatory is no exception to the claustrophobic aesthetic.

My six minute presentation couldn’t quite cover “Wharton to Waugh”, or

“Newland Archer’s thoughts on “queer cosmopolitan women … too much like expensive and rather malodorous hot-house exotics, to detain his imagination long” (Wharton, Ch. 20).”

“Transcending Glass - The Greenhouse Effect on Page and Screen.” Robyn Coombes. 31 Jan, 2023.

But the expanded form of a blog allowed me to investigate the significance of Northanger Abbey’s “village of hot-houses” and its pinery yielding a hefty hundred pineapples a year (197), alongside the imperial implications of the contested space of the hothouse -

“teeming with a profusion of tropical or Mediterranean species of Otherness, these transparent forcing houses both flaunted the spoils of empire and taunted with microcosms of the barely controllable. As Dominic Rainsford asserts in a review of The Hothouse Flower: Nurturing Women in the Victorian Conservatory, “the imperial commodity could cross the glass membrane and become a disruptive force”. The threat of the Other was reified in these exoticised displays, which Margaret Flanders Darby asserts, could become viable and invasive species if allowed to escape their glass containment (32).

“Transcending Glass - The Greenhouse Effect on Page and Screen.” Robyn Coombes. 31 Jan, 2023.

From my suspicions that “these spaces often function as the site of secret trysts, coy flirtations, or even indecent proposals”, I consulted Jane Desmarais’s illuminating Monsters Under Glass: A Cultural History of Hothouse Flowers from 1850 to the Present, which acknowledges the proliferation of the conservatory’s "amatory and often clandestine encounters" (128) within the context of exoticised (and eroticised) hothouse flowers and the phenomenon of the "fleur fatale".

“According to Mary Bowden’s review of Desmarais’s book, this flower power woman “renovat[es] older associations between women and flowers to encompass dangerous or seemingly degenerate New Women”.”

“Transcending Glass - The Greenhouse Effect on Page and Screen.” Robyn Coombes. 31 January, 2023.

Fig. 20. Still from Chéri, directed by Stephen Frears, Pathé, 2009. Michelle Pfeiffer as fleur fatale.

These findings will undoubtedly inform my thesis, which concerns itself with Austen’s use of greenhouse metaphors and associations between women and hothouse fruits. But scanning through my blogging history, I realise that everything I've consulted and considered along the way has brought me on a scenic route of research that will surely pave the way to a destination of sorts.

What began as another thing to fret about has truthfully evolved into an enjoyable ramble through diverse topics, diverting illustrations, and illustrative essays, which I hope to continue after a brief hiatus. Alongside our formal academic essays, this became a channel for casual considerations that helped me map my merry way towards the terrifying land of Thesis. But with some miles under my belt now, I’m hoping the acres before me might be more easily navigated. Expect far more forays into children’s books, contemporary women’s literature, and detective fiction in the future, once I’ve slain those pesky dissertation-dragons.

There be dragons indeed

Works Cited

Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Glassworlds: Glass Culture and the Imagination 1830-1880. Oxford UP, 2008.

Austen, Jane. Mansfield Park. 1814. Headline Review, 2006.

---. Northanger Abbey. 1818. Penguin Red Classic, 2006.

---. Pride and Prejudice. 1813. Project Gutenberg, 2022.

Barklem, Jill. The Complete Brambly Hedge, HarperCollins, 2020.

Barrie, J.M. Peter Pan. 1911. Penguin, 1995.

Bowden, Mary. Review of Monsters under Glass: A Cultural History of Hothouse Flowers

from 1850 to the Present, by Jane Desmarais. Victorian Studies, vol. 61 no. 3, 2019, p.

516-517. Project MUSE, muse.jhu.edu/article/734988.

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. 1847. Penguin, 1994.

Darby, Margaret Flanders. The Hothouse Flower: Nurturing Women in the Victorian

Conservatory. Edward Everett Root, 2020.

Denton, Danny. “Being Present: how ideas of physical space, place & non-place were used to

build the worlds of The Earlie King… and All Along The Echo.” Spring Seminar Series,

University College Cork, 1 Feb. 2023.

Desmarais, Jane. Monsters under Glass: A Cultural History of Hothouse Flowers from 1850

to the Present. Reaktion Books, 2018.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist or, The Parish Boy’s Progress, edited by Philip Horne, Penguin Classics, 2009.

Dreifus, Claudia. “Elizabeth Gilbert Finds Inspiration Behind the Garden Gate.”

The New York Times, 4 Nov. 2013, www.nytimes.com/2013/11/05/science/

Evans, Heather A. “Kittens and Kitchens: Food, Gender, and ‘The Tale of Samuel

Whiskers.’” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 36, no. 2, 2008,

pp. 603–23. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40347207.

Gaskell, Elizabeth. North and South. 1854. Project Gutenberg, 2001.

---. Wives and Daughters. 1866. Penguin, 2003.

Gilbert, Elizabeth. The Signature of All Things. Bloomsbury, 2013.

“How It All Began.” Brambly Hedge, www.bramblyhedge.com/our-story/.

Hudson, Glenda A. “Incestuous Relationships: Mansfield Park Revisited.” Eighteenth-Century Fiction,

vol. 4, no. 1, 1991, pp. 53-68. Project Muse, doi.org/10.1353/ecf.1991.0009.

Hughes, Kathryn. "Review: Arts: Run Rabbit Run . . .: Beatrix Potter Isn't all

Fluffy Animals and Cosy Interiors. There's Danger Lurking Everywhere.

Kathryn Hughes on the Amateur Watercolourist Who Stormed the Nursery."

The Guardian, Oct 08, 2005, pp. 1-4. ProQuest, www-proquest-com.ucc.idm.oc

lc.org/newspapers/review-arts-run-rabbit-beatrix-potter-isnt-all/docview/2463

46771/se-2.

Hughes, Thomas. Tom Brown’s Schooldays. 1857. Puffin, 1971.

Hunt, Peter. “Introduction: The Expanding World of Children’s Literature Studies.”

Understanding Children’s Literature, edited by Peter Hunt, Taylor & Francis, 2005,

pp. 1-14. ProQuest, www.ebookcentral-proquest-com.ucc.idm.oclc.org/lib/uccie-eb

ooks/detail.action? docID=259048.

Kent, Hannah. The Good People. Picador, 2017.

Kincaid, James R. “Dickens and the Construction of the Child.” Dickens and the Children of Empire,

edited by Wendy S. Jacobson, Palgrave, 2000, pp. 29-42.

Kosman, Marcelle, and Hannah McGregor. Witch, Please, 2022, www.ohwitchplease.ca.

Kutzer, M. D. "A Wildness Inside: Domestic Space in the Work of Beatrix Potter."

The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 21, no. 2, 1997, pp. 204-214. ProQuest, www.pr

oquest.com/scholarly-journals/wildness-inside-domestic-space-work-beatrix.d

Mansfield Park. Directed by Patricia Rozema, performances by Frances O’Connor, Jonny Lee Miller, Harold Pinter,

Lindsay Duncan, Embeth Davidtz, Alessandro Nivola, James Purefoy, Hugh Bonneville, and Victoria Hamilton,

Miramax, 1999.

Martin, Maureen M. “‘Boys Who Will Be Men’: Desire in Tom Brown’s Schooldays.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 30, no. 2, 2002, pp. 483–502. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25058601.

Potter, Beatrix. Beatrix Potter: Drawn to Nature. 12 Feb. 2022 - 8 Jan. 2023, The Victoria and Albert

Museum, London.

---. The Tailor of Gloucester. 1903. Frederick Warne & Co, New York, 1931, pp. 1-85.

Rainsford, Dominic. Review of The Hothouse Flower: Nurturing Women in the Victorian

Conservatory by Margaret Flanders Darby. Dickens Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 4,

2021, pp. 474-478. ProQuest, www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/i-hothouse-flower-

nurturing-women-victorian/docview/2604871423/se-2.

Reimer, Mavis. “Traditions of the School Story.” The Cambridge Companion to Children’s

Literature. Cambridge UP, 2009, pp. 209-225.

Rodgers, Beth. “LT Meade, the JK Rowling of her day, remembered 100 years on.” The Irish Times, 26 Oct. 2014,

1.1977221.

Scott, Carole. "Clothed in Nature or Nature Clothed: Dress as Metaphor in the

Illustrations of Beatrix Potter and C. M. Barker." Children's Literature, vol. 22,

1994, p. 70-89. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/chl.0.0559.

---. “Between Me and the World: Clothes as Mediator between Self and Society in the

Work of Beatrix Potter.” The Lion and the Unicorn (Brooklyn), vol. 16, no. 2, 1992,

pp. 192-198.

Seward, Anna. “Sonnet LXIII: To Colebrooke Dale”. The Victorian Web, 22 Aug. 2018,

Shteir, Ann B. “Gender and “Modern” Botany in Victorian England.” Osiris, vol, 12,

1997, pp. 29-38.

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection, Duke UP,

1993.

Walker-Dunseith, Holly M. “The Healer in the Tower: Biddy Early and Discourses of

Healing in the Work of W. B. Yeats and Lady Augusta Gregory.” Irish Studies

Review, vol. 30, no. 3, 2022, pp. 340-356.

Wallace, Karen. Wendy, Simon and Schuster, 2003.

Waugh, Evelyn. Brideshead Revisited: The Sacred & Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder.

1945. Project Gutenberg, 2019.

Wharton, Edith. The Age of Innocence. 1920. Project Gutenberg, 2008.

Comments